How I collect telemetry from Batect users

I’m constantly asking myself a bunch of questions to help improve Batect: are Batect’s users having a good experience? What’s not working well? How are they using Batect? What could Batect do to make their lives easier?

I first released Batect back in 2017. Since then, the userbase has grown from a handful of people that could fit around a single desk to hundreds of people all over the globe.

Back when everyone could fit around a desk, answering these questions was easy: I could stand up, walk over to someone, and ask them. (Or, if I was feeling particularly lazy, I could stay seated and ask over the top of my screen.)

But with this growth, now I have another question: how do I break out of my bubble and feedback and ideas from those I don’t know?

This is where telemetry data comes into the picture. Besides signals like GitHub issues, discussions, suggestions and the surveys I occasionally run, telemetry data has been invaluable to help me get a broader understanding of how users use Batect, the problems they run into and the environments they use Batect in. This in turn has helped me prioritise the features and improvements that will have the greatest impact, and design them in a way that will be the most useful for Batect’s users.

In this (admittedly very long) post, I’m going to talk through what I mean by telemetry data, how I went about designing the telemetry collection system, Abacus, and finish off with two stories of how I’ve used this data.

- Telemetry?

- Key design considerations

- The design

- Examples of where I’ve used this data

- What works well, and what doesn’t

- In closing

Telemetry?

Similar to Honeycomb’s definition of observability for production systems, I wanted to be able to answer questions about Batect and it’s users I haven’t even thought of yet, and do so without having to make any code changes and push out a new version of Batect.

This is exactly the problem that Batect’s telemetry data solves. Every time Batect runs, it collects information like:

- what version of Batect you’re using

- what operating system you’re using

- what version of Docker you’re using

- a bunch of other interesting environmental information (what shell you use, whether you’re running Batect on a CI runner or not, and more)

- data on the size of your project

- what features you are or aren’t using

- notable events such as if an update nudge was shown, or if an error occurred

- timing information for performance-critical operations such as loading your configuration file

…and more! There’s a full list of all the data Batect collects in its privacy policy.

With this data, I can answer all kinds of questions. Here are just a few real examples:

- How long does it take for new versions of Batect to be adopted? (answer: anywhere from hours to months, depending on the user)

- How many times does a user see an update nudge before they update Batect? (answer: lots - some users even seem to never respond to these)

- Does using BuildKit really make a difference to image build times? (answer: yes)

- Could adding shell tab completion really be useful? (answer: yes, humans make lots of typos)

- Was adding shell tab completion actually useful? (answer: yes, it prevents lots of typos)

- What’s the common factor behind this odd error that only a handful of users are seeing? (answer: one particular version of Docker)

Key design considerations

There were a couple of key aspects I was considering as I sketched out what the telemetry collection system could look like, in rough priority order:

-

Privacy and security: given the situations and environments where Batect is used, preserving users’ and organisations’ security and privacy are critical. This is not only because it’s simply the right thing to do, but because any issues here would likely lead to a loss of trust and to them blocking telemetry data or not using Batect, which is obviously not what I want.

-

User experience impact: Batect is part of developers’ core feedback loop, and so any changes that made it noticeably less reliable or less performant were non-starters.

-

Cost: any expense to build or run the system would be coming out of my own pocket, so minimising the cost was important to me.

-

Ease of maintenance: this is something I largely maintain in my own time, so minimising the amount of ongoing care and feeding was another high priority. Another aspect of maintenance was also designing something simple and easy to understand, so that when I come back to do any future maintenance, I wouldn’t need to spend a lot of time re-learning a tool, service or library.

-

Flexibility: I want to be able to investigate new ideas and answer questions I haven’t thought of yet, as well as expand the data I’m collecting as Batect evolves, and so I needed a system that supports these goals.

-

Learning: given I was building this on my own time, I also wanted to use this as an opportunity to learn more about a few technologies and techniques I hadn’t used much before.

The design

It’s probably easiest to understand the overall design of the system by following the lifecycle of a single session.

A session represents a single invocation of Batect - so if you run ./batect build and then ./batect unitTest, this will create two telemetry sessions,

one for each invocation.

1️⃣ As Batect runs, it builds up the session, recording details about Batect, the environment it’s running in and your configuration, amongst other things. It also records particular events that occur, like when an error occurs or when it shows you a “new version available” nudge, and captures timing spans for performance-sensitive operations like loading configuration files.

Just before Batect terminates, it writes this session to disk in the upload queue, ready to be uploaded in a future invocation.

2️⃣ When Batect next runs, it will launch a background thread to check for any outstanding telemetry sessions waiting in the upload queue.

3️⃣ Any outstanding sessions are uploaded to Abacus. Once each upload is confirmed as successful, the session is removed from disk.

4️⃣ Once Abacus receives the session, it performs some basic validation and writes the session to a Cloud Storage bucket. Each session is assigned a unique UUID by Batect when it is created, so Abacus uses this ID to deduplicate sessions if required.

5️⃣ Once an hour, a BigQuery Data Transfer Service job checks for new sessions in the Cloud Storage bucket and writes them to a BigQuery table.

6️⃣ With the data now in BigQuery, I can either perform ad-hoc queries over the data to answer specific questions, or use Google’s free Data Studio to visualise and report on the data.

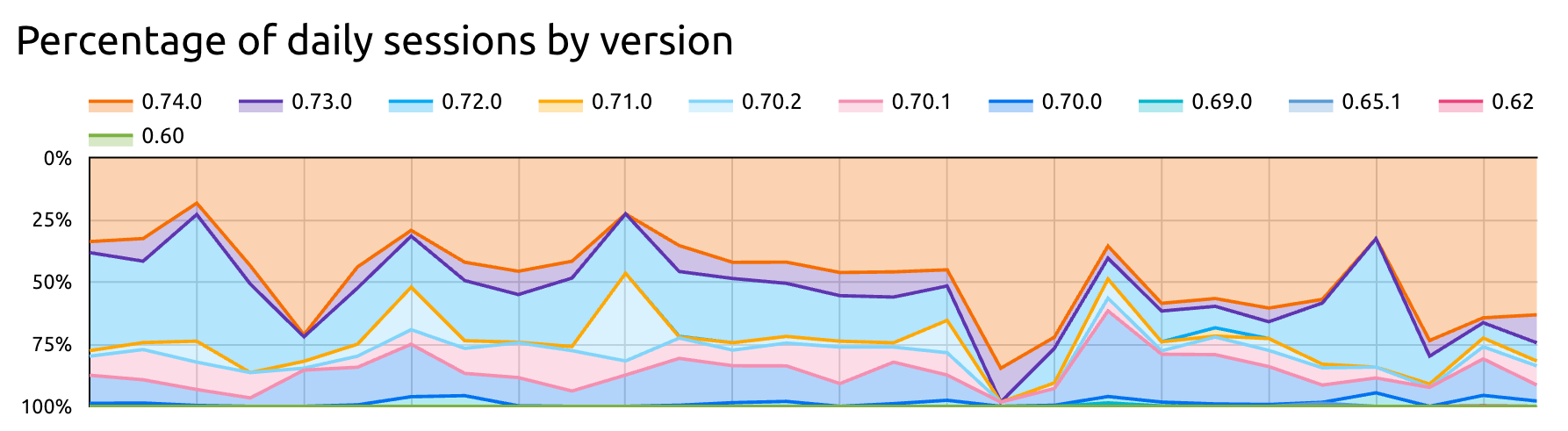

For example, I can report on what version of Batect is being used:

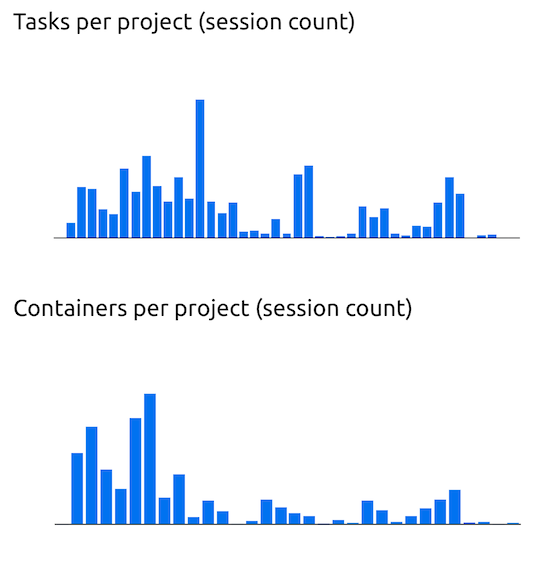

Or the distribution of the number of tasks and containers in each project:

There a bunch of other important details I’ve skipped over here in the interest of brevity - topics like not collecting personally identifiable information, or even potentially-identifiable information and managing consent - but these are all important aspects to consider if you’re thinking of building a similar system yourself.

Examples of where I’ve used this data

Some of my favourite stories of how I’ve used this data are for prioritising Batect’s shell tab completion functionality and validating that it had the intended impact, and for prioritising contributing support for Batect to Renovate.

Shell tab completion

Batect’s main user interface is the command line: to run a task, you execute a command like ./batect build or ./batect test from your shell.

One of the most frequently-requested features was support for shell tab completion, so that instead of typing out build or test, you could type

just the first letter or two, press Tab, and the rest of the task name would be completed for you.

While I could definitely see the value in this, I was worried I was over-emphasising features I’d like to see based on how I usually work and interact with applications, and wanted to confirm that this would actually be valuable for a large portion of Batect’s userbase. I formed a hypothesis that shell tab completion would help reduce the number of sessions that fail because the task name cannot be found, likely because of a typo.

So, I turned to the data I had and found that roughly 2.6% of sessions fail because the task cannot be found. This seemed very high and was enough for me to feel confident investing some time and effort implementing shell tab completion.

Of course, the next question was which shell to focus on first: Bash? Zsh? My personal favourite, Fish? My gut told me most people would likely be using Zsh or Bash as their default shell, but here the data told a different story: the shells used most commonly by Batect’s users are actually Fish and Zsh. So that’s where I started - I added tab completion functionality for both Fish and Zsh - and, thanks to the data I had, I was able to prioritise my limited time to focus on the shells that would help the largest number of users.

And, thanks once again to telemetry data, once I’d released this feature, I was also able to quickly validate my hypothesis: users that use shell tab completion experience “task not found” errors over 30% less than those that don’t use it.

Renovate

Batect is driven by the batect and batect.cmd wrapper scripts that you drop directly into your project and commit alongside your code.

Most of the time, this is great: you can just clone a repository and start using it without needing to install anything, and you can be confident everyone on your team is using exactly the same version.

However, there’s a drawback hiding in the last part of that sentence: this design also means that you or one of your teammates must upgrade the wrapper script to use a new version of Batect. Based on both anecdotal evidence from users asking for features that already existed, as well as telemetry data, I could see that many teams were not upgrading regularly. And from telemetry data, I also knew this was happening even while users were seeing an upgrade nudge like this many hundreds of times a day:

Version 0.79.1 of Batect is now available (you have 0.74.0).

To upgrade to the latest version, run './batect --upgrade'.

For more information, visit https://github.com/batect/batect/releases/tag/0.79.1.

Armed with this information, I decided to try to help users upgrade more often and more rapidly - there was little point spending time building new features and fixing bugs if only a small proportion of users benefited from these improvements.

My solution was to add support for Batect’s wrapper script to Renovate. This means that projects that use Renovate will automatically receive pull requests to upgrade to the new version whenever I release a new version of Batect, and upgrading is as simple as merging the PR.

Again, the data shows this has been a success: whereas previously, a new version would only slowly be adopted, now, new versions of Batect make up over 40% of sessions within a month of release.

What works well, and what doesn’t

The Abacus API is a single Golang application deployed as a container to GCP’s Cloud Run. I’ve been really happy with Cloud Run: it just works. My only wish is that it had better built-in support for gradual rollouts of new versions. This is something that can be done with Cloud Run, but as far as I can tell, it requires some form of external orchestration to monitor the new version and adjust the proportion of traffic going to the new and old versions as the rollout progresses.

Cloud Run also integrates nicely with GCP’s monitoring tooling. I wasn’t sure about using GCP’s monitoring tools at first - I was expecting that I’d quickly run into a variety of limitations and rough edges like with AWS’ CloudWatch suite - but I’ve been pleasantly surprised. For something of this scale, the tools more than meet my needs, and I haven’t felt the need to consider any alternatives. I recently added Honeycomb integration, but this was more out of curiousity and wanting to learn more about Honeycomb than a need to use another tool.

The pattern of dropping session data into Cloud Storage to be synced by BigQuery Transfer Service into BigQuery has also been more than sufficient for my needs. While this does introduce a delay of up to two hours between data being received and it being ready to query in BigQuery, I rarely want to query data so rapidly, and the alternative of streaming data would be both more complex and more costly.

All of this also almost fits within GCP’s free tier: the only item that regularly exceeds the free allowance is upload operations to Cloud Storage, as each individual session is uploaded individually as a single object, and the free tier includes only 5,000 uploads per month. I could reduce this cost by batching sessions together and uploading a batch as a single file, but this would again introduce more complexity and cost for little benefit.

On the client side, the concept of the upload queue has been really successful: uploading sessions in the background of a future invocation minimises the user impact of uploading this data, and provides a form of resilience against any transient network or service issues. (If a session can’t be uploaded for some reason, Batect will try to upload it again next time, or give up once the session is 30 days old.)

The biggest area for improvement is how I manage reports and dashboards. I’m currently using Data Studio for this, and while it too largely just works, there are a couple of key features missing that I’d really like to see. For example, it’s not possible to version control the definition of a report, making changes risky, and doesn’t have built-in support for visualisations like histograms or heatmaps, limiting how I can visualise some kinds of data.

In closing

Collecting telemetry data is something I wish I’d added to Batect far earlier. But now that I have this rich data, I can’t imagine life without it. It’s helped me prioritise my limited time and enabled me to deliver a more polished product to users.

On top of this, I’ve achieved my design goals for Abacus, including preserving users’ privacy and minimising the performance impact of collecting this data. And I’ve learnt about services like BigQuery and Data Studio along the way.

If you’re interested in checking out the code for Abacus, it’s available on GitHub, as is the client-side telemetry library used by Batect.

Updated July 10 to include more details of the tools and services behind Abacus.